University camps under Austrofascism

With the Hochschulerziehungsgesetz (university education law) of 1935, the Austrofascist government introduced university summer camps, so-called “Hochschullager”. These camps held in 1936 and 1937 were mandatory for all male students and had the goal of militarizing them mentally and physically. They were places of elite ideological community- and nation-building, raising “new Austrians” – contrasting the National Socialist identity of the German Reich. Through the community experience of several weeks of shared camp life, the new Austrian people’s community was meant to be experienced. A Catholic-German Austria was supposed to assert itself against Hitler’s Germany, while the youth was trained in Austrian patriotism. Paramilitary training furthermore was intended to militarize the students, but was used more for infusing discipline than for actual military training.

Austria’s mission

In the 1920s the University of Vienna was a stronghold of the ideologies of Greater Germany and the Reich. Particularly at the Faculty of Law and Economics, professors such as Othmar Spann represented a romantic social philosophy based on the Middle Ages and Catholicism. Engelbert Dollfuß had studied under Spann and like many others saw in National Socialism a bastion of German culture and even the realization of the medieval Reich concept. But Hitler’s Germany went down another path – a non-Christian and anti-corporative one. Subsequently, some ideologists saw Austria’s mission in retaining the European-western idea of the Reich. When Dollfuß adopted his authoritarian course as Chancellor in 1933, he focused on the establishment of a Catholic corporative state, in which Austria was to be an example for the rest of Europe as a better Germany. This double mission – inner-German and European – resulted in the ultimately impossible balancing act of fighting National Socialism while not relativizing the Greater German idea.

Militarization at the university

After the murder of Chancellor Dollfuß in 1934, the Austrofascist dictatorship was established under a perceived threat from Hitler-Germany. It was necessary to find (or invent) the specifically Austrian aspects of German culture as part of western Christianity and to build the “Austrian people’s” militarization on this. For this purpose, the new government under Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg pursued the militarization of all areas of life. At the university, this expressed itself through mental and physical training. With significant help by professor of law Ludwig Adamovich, two university laws were announced in July 1935, which would regulate ideological access to the university and the students: the Hochschulermächtigungsgesetz (university empowerment law) and the Hochschulerziehungsgesetz (university education law). The latter added a third function to the university’s existing two (research and teaching): citizen education. This was done through mandatory ideological lectures, pre-military exercises (i.e. at university shooting ranges) and with “university camps”. These camps had to be attended by all male students of secular disciplines with an Austrian citizenship so as to be admitted to the graduation exams. Women were neither forced to attend nor were they allowed to volunteer.

Community building at university camps

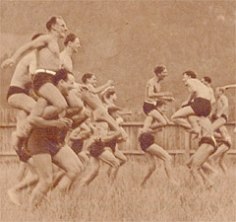

The university camps were aimed at militarizing students both physically and mentally. Through the communal experience of several weeks of shared camp life, the new Austrian people’s community was meant to be experienced. Pre-military training (exercise, strength training, camouflage, map reading etc.) was an attempt at partially compensating for the lack of general conscription until 1936 and at enlisting the older “white” age groups of students who had not served in the military. In actual fact, however, the military drills were used more to infuse discipline than as real military training. Students were supposed to be made fit for the community and to overcome their individuality. In the camp, students, “weak, pale city people”, should become “strong and tanned” like the country boys (Ignaz Zangerle), and be sworn to the new Austrian ideology. To that effect, every camp was led by an officer of the Austrian Armed Forces, aided by a chief of education. The former was responsible for the pre-military training and physical exercise, while the latter saw to the ideological education in accordance with the Fatherland ideology (i.e. not National Socialist, not liberal and certainly not social democratic, but western-Christian-German).

Daily camp routine

The university camps were located in Rotholz bei Jenbach, Ossiach and in Kreuzberg at the Weißensee. Due to Austria’s Anschluss to the German Reich, they were only held twice, in the summers of 1936 and 1937. The participants were dressed in uniform clothing and had a strict camp schedule during the four weeks they were there:

06:00: Wake-up call

06:15-06:45: Morning exercises, possible swimming in the lake

07:00: Breakfast

07:10-07:40: Tidying the rooms

07:45-08:00: Raising the flag, announcement of the day’s schedule, presentation of the sick, camp report

08:05-10:00: Exercises, class; if necessary second breakfast at 10:00

10:30-12:30: Shooting practice, physical exercise

13:00-13:30: Lunch

13:30-14:30: Midday break

14:30-15:00: Lecture by the chief of education

15:00-16:00: Physical exercise at the lake shore; if necessary snack at 16:00

16:30-18:30: Exercises or lecture by the chief of education, issuing of orders, roll call

19:00-19:20: Dinner

20:00-21:15: Free time

22:00: Curfew

From 22:30: No more talking, complete silence in the building

Robert Hampel remembers the camp he attended at the Weißensee in 1937: “At the time, Hitler-Germany gave its students additional tasks such as harvest duties and training, so Schuschnigg-Austria also wanted to give its students a pre-military education and influence them ideologically-politically in the interests of the ‘Vaterländische Front’ (‘Fatherland’s Front’) … I was one of the first to arrive at the Kreuzberg … Everything was represented – from lederhosen to city suits – but in the coming weeks only the cheaply procured camp pants and grey-green-colored windbreakers counted … The most remarkable figure in this camp was the so-called chief of education … Three times a week he took us under his wing. He taught us about student issues, our relationship to the people’s community, to the state, and to farmers and soldiers.”

Austrofascist education

The goal of the university-political measures attempting to shape an Austrian ideology was (mental) militarization particularly against Hitler-Germany. However, this was done by means similar to those used by the National Socialists. In both cases, the intrusion of militaristic elements into the pedagogical discourse is the key to understanding fascist education. Also in both cases, the preferred educational method in creating a new community-minded person was the camp. It did not emphasize individuals, but the group, which in turn was ordered in a hierarchy emulating the military under a group leader (camp leader, chief of education). Social background and level of education became secondary; only a strong body and a community spirit were important. Thus, the introduction of mandatory university camps was aimed at two things: On the one hand, the class struggle that had reached its bloody peak in the civil war of 1934 was meant to be overcome while creating an all-encompassing Austrian community; on the other hand, these groups of men were trained both physically and militarily – ultimately they were trained in discipline. As becomes clear from various accounts (see Hampel and Zangerle), the communal experience was the key element of camp life. Here the new Austria could be experienced.

Zuletzt aktualisiert am : 30.04.2022 - 18:40