The Castalia Fountain in the Arkadenhof of the University of Vienna

In the middle of the Arkadenhof (arcaded courtyard) in the main building, in the center of the University of Vienna’s memorial topography, Castalia sits enthroned. In Greek mythology, she is the guardian of the fountain of knowledge in Delphi. This fountain statue erected around 1900 symbolizes the wisdom of the men whose monuments surround her in the Arkadenhof – the first and only monument for a woman was unveiled later, in 1925. In historical context her meaning is much more diverse, however: She stood for a male dominated civil society that discriminates against women, protesting against the ruling system. Her relevance as a symbol for a misogynistic university was especially long-lived. In 2009, finally, this level of meaning was broken by the inclusion of the Castalia fountain into Iris Andraschek’s art project “Der Muse reicht’s” (“The muse has had it”).

Historical origin

With the opening of the Viennese university building in 1884, the Academic Senate began – based on plans by architect Heinrich v. Ferstel – erecting monuments for important scientists in the Arkadenhof. At the time, no women were among them. In the center, Ferstel had envisioned an equestrian statue for the university’s founder, Duke Rudolf IV. Presumably out of financial concerns, this plan was not implemented. In November 1893, the then Minister for Culture and Education, Stanislaw Madeyski, informed the rectorate that he wanted to erect a monument created by sculptor Anton Paul Wagner and that he was ready to procure the necessary funds for it: The “Nymph Castalia with the Dragon Python”. He gave no reason for his decision. The rectorate agreed and due to Wagner’s death in 1895 commissioned sculptor Edmund Hellmer with the statue. Fifteen years later, in August 1910, the monument was erected.

Mythological background

The mythological tale of the fountain nymph Castalia saw many variations over the centuries. Here just some aspects of this story will be presented – those that were taken into regard when the statue was designed. On both sides of Castalia’s throne Greek inscriptions talk of Castalia herself: “I am Castalia, daughter of Achelous” and “My sleep is dreams, but by dream became knowledge”. The first sentence describes the figure and references her history: Castalia was the daughter of river god Achelous. She fled from Apollo, who was pursuing her, and in order to evade him, she threw herself into the spring at Delphi and drowned. Subsequently, Apollo made her the guardian of the spring. The second inscription was written by Hans von Arnim (professor of classical philology at the University of Vienna from 1900 to 1914 and from 1921 to 1930), based on a line from Richard Wagner’s opera “Siegfried”. It references the part of the Castalia myth in which she becomes the guardian of the spring of knowledge.

A snake made out of metal and not – like the rest of the fountain figure – out of stone is coiled around the throne. It seems like an attachment to the statue, as if it did not quite belong to it, and yet it is of great importance when interpreting the monument. The snake in question is the dragon Python. The mythological tales about it are almost more varied than the ones about Castalia. A relief on the back of the figure references a special moment in the stories: A strong, young, naked man is throttling a snake. It symbolizes Apollo killing Python. Before the Olympic god Apollo was revered in Delphi, the temple was dedicated to the earth goddess Gaia. Her guardian of the sacred spring was Python. This change from one cult to another found its way into various versions of the myth, all having in common that Apollo’s takeover was violent: Apollo kills Python.

Female allegories in monuments

In her habiliation paper, art historian Silke Wenk analyzed national monuments in Prussia from the 19th and 20th centuries. She focused on function and meaning of female allegories in regard to these monuments. Wenk had noticed that these figures were often used to represent values and institutions to which women had no access: victory, nation, science, etc. They were also often designed differently than figures representing real women – they were for example dressed more scantily – and they had a different function than representations of female role models such as farmers or soldiers’ wives. Silke Wenk came to the conclusion that in late 19th century Prussia female allegories replaced the ruler-body, the representation of monarchical state power, and had “an important function in the formation of a national consciousness and in the organization of a new form of ideological-cultural cohesion” (Wenk 1996, 92). The Viennese university building was erected as a state institution, whose Arkadenhof resembles a national monument in its role as a place of remembrance for great (male) scientists – Elise Richter was the first woman to receive an associate professorship as late as 1921, and Berta Karlik was the first to receive a full professorship in 1956. If one analyzes the statue based on Silke Wenk’s work, following picture emerges:

Summary

When the monarchy still was Austria’s form of government, Castalia as the reference point in the center of the University of Vienna’s remembrance topography broke through the monarchic symbolism of power. This was ubiquitous in the building’s structure at the time the university was constructed and it largely remains omnipresent until today. However, in the Arkadenhof almost no symbols of the former ruling house can be found. Through the female allegory the educated middle class imagined a change of government, just as in the myth Apollo drives away the old goddess and kills Python. This symbolic revolutionary thought is strengthened by the reference to Richard Wagner in the second Greek inscription on Castalia’s throne – at the time, Wagnerism stood for political modernization.

The new system was not meant to be dominated by women, as Castalia as a female allegory might lead one to believe. “The female allegories represent the opposite of the feminine, they do not represent women, but the power of ruling, which even the ‘great men’ often lack and which transcends them” (Wenk 1996, 101). The female body constructed as a female allegory and whose femininity is erased symbolically was simply a projection surface for a new civil society in which men rule. Thus, Castalia remains in her role as a tragic victim of male desire. In summary, the self-conception of the educated, republican civil society that imagined itself in the University of Vienna’s Arkadenhof around 1900 can be described thusly: Men rule, women devote themselves to them.

Iris Andraschek designed her 2009 art project „Der Muse reicht’s“ (“The muse has had it”) as an explicit response to this discriminatory symbolism and because of this chose the Castalia fountain as a central reference point.

-

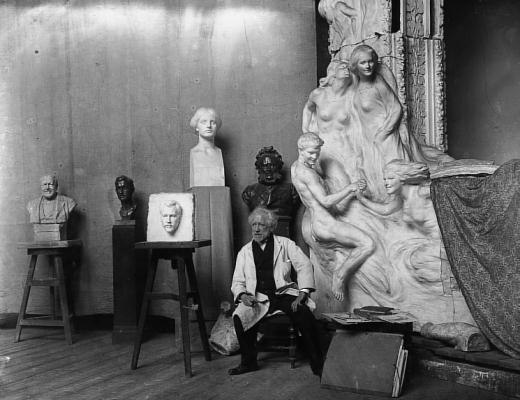

Edmund Hellmer (1850–1935) in seinem Atelier, 1923 – im Hintergrund der Kopf der Kastalia

-

Kastaliabrunnen von Edmund Hellmer (Rückseite)

Relief von Appollon, die Schlange Phython würgend

-

Kastaliabrunnen von Edmund Hellmer im Arkadenhof, um 1965 nach der Neugestaltung des Hofes

-

Kastalia von Edmund Hellmer, 1910, und Kunstprojekt „Der Muse reichtʼs“, Kunstprojekt von Iris Andraschek 2009

Last edited: 01/19/17