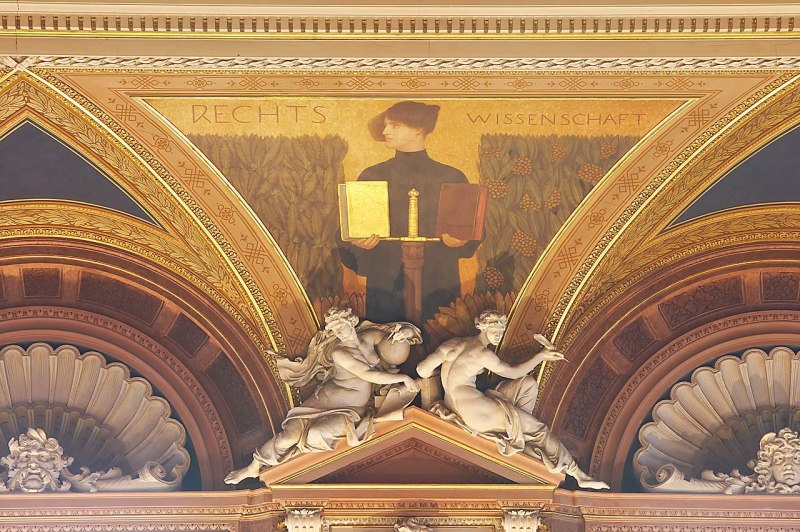

Law and Economics, part I

With its more than six hundred-year-old history, the jurists can look back at one of the longest traditions at the University of Vienna. Their faculty’s curriculum, originally limited to canonical and Roman law, was extended regularly since the 18th century. This not only included legal disciplines, but also disciplines outside of jurisprudence, particularly economics and statistics, which led to the faculty changing its name in 1848 to “Faculty of Law and Economics”.

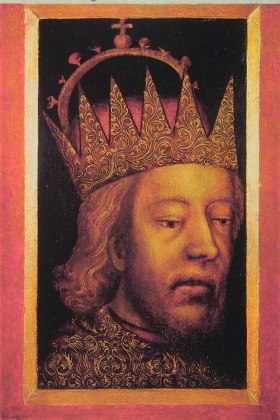

In the university’s founding letter by Rudolphs IV. from March 12, 1365, a study of “Iura Canonica et civilia” was already proclaimed, the study of ecclesiastical and civil law. However, until 1402 no regulated studies could be established and they were limited to canonical law for almost a century. In 1494, finally, Hieronymus Balbi’s appointment from Venice was able to establish the study of civil law at the university. As was usual for the time, this was taught based on the Corpus Iuris Civilis, a collection of texts on classical Roman law which had been compiled around AD 533 at the behest of Emperor Justinian I. Local, often not yet recorded, law, which was handled by the courts was thus not part of the academic education until the 17th century and after that it was also only taken into account in the sense that single institutions of local law were slowly integrated into the dogmatic discussion of the “taught law”, resulting in the Ius Romano-Germanicum.

In 1753 the Faculty of Law was completely reorganized by Maria Theresia, who furnished the faculty with five professorial chairs and significantly broadened the curriculum. In particular, natural law found its way into the faculty with the appointment of Karl Anton von Martini. Martini’s successor, Franz von Zeiller, developed the new curriculum of 1810, with which natural law was firmly entrenched in the faculty by making it an introductory course into law. During that time, the codification of Austrian criminal and civil law begun under Maria Theresia was concluded, so that the lectures could now be held based directly on the Criminal Code and the Civil Law Code.

“Statistics” first became an examination subject in 1810. At the time it mainly had the description of the state of the Austrian monarchy as its subject, combining topics that today would probably be more appropriate for geography, ethnology or contemporary history. However, the basics of the political order (one cannot really speak of “constitutional law” in the era of absolutism) were also taught here. Gradually, as a consequence of establishing modern constitutional law through Moriz von Stubenrauch in 1850, the discipline of statistics was transformed, losing its old subject matter. Inferential statistics were added to the descriptive statistics, being more mathematically oriented and laying the foundation for the development of modern social and economic sciences. These modern statistics also led to the increased use of electronic calculators, thus becoming the birthplace of today’s Faculty of Informatics.

The study of law experienced a far-reaching reorientation following the university reform of Minister Leo Graf Thun-Hohenstein. With the curriculum of 1855, natural law, which was at least given partial responsibility for the (failed) revolution of 1848, was largely abolished. In its place, the legal-historical disciplines dominated the first stage of studies – Roman law, German legal history and German private law. The minister hoped to thus link up with German jurisprudence and to “educate” the law students to become patriotic-conservative citizens. His plans did not work out and in all following reforms the importance of the legal-historical disciplines was gradually diminished. While canonical law as a mandatory subject disappeared from the curriculum in 1978, Roman law and legal history – thematically significantly modernized and scaled down by about 80% of its content – have kept their place in the beginning of the study of law due to their didactically valuable function as remedial courses on established law.

Joseph Unger’s appointment to a civil law chair in 1856 can also be traced back to Thun-Hohenstein’s university reform. Unger became the most important representative of so-called pandectistics in Austria, an academic movement from Germany that studied Roman Pandects in order to solve problems of established law. Pandectistics’ main result are the so-called part-amendments of the General Civil Code from the years 1914, 1915 and 1916, with which the Austrian Civil Code was modernized and partially aligned with the German Civil Code of 1896.

Pandectistics was heavily criticized in Austria due to its alleged unworldliness (“conceptual jurisprudence”) and because it failed to take social conditions into account. One of its largest critics was civil proceduralist Anton Menger, who severely criticized the German Civil Code as the code of law of a capitalist social order. Menger’s student Franz Klein became the founder of the Austrian civil code of procedure, an internationally much lauded law that gave the judge an active role in the trial. Critics of conceptual jurisprudence also included Rudolf Jhering, who laid the foundation for principle-based jurisprudence, which is predominant in today’s civil jurisprudence, with his lecture “Der Kampf ums Recht” (“The fight for the law”) at the Wiener Juristische Gesellschaft (Viennese Society of Law) on March 11, 1872.

Last edited: 04/20/17

-

Law and Economics, part II

1893–2015

-

Rudolf IV. (Habsburg), Herzog von Österreich, Beiname „der Stifter“

-

Maria Theresia von Österreich (Habsburg)

-

Karl Anton Freiherr von Martini zu Wasserburg

-

Franz Anton Edler von Zeiller

-

Moritz von Stubenrauch

-

Josef Unger

-

Anton Menger von Wolfensgrün

-

Franz Klein

-

Rudolf von Jhering

-

Anton Josef Hye Freiherr von Glunek