The university’s leadership from the 14th to the 19th century

Magnifice Domine Rector et Venerabile Consistorium: This title, to be found on many documents from the early Modern Age, names the university’s highest authorities: the rector as elected head of the university, who oversaw the official duties together with the Consistory, which was formed by the heads of the individual corporations.

In the Middle Ages and the early Modern Age, the university consisted of different sub-corporations like faculties and nations, which each represented separate legal bodies. These separate entities took care of their own official business, but were also integrated into the university’s general administration through deans and procurators. At the head of the overall corporation stood the head of the “community of teachers and students”, called the rector, who was elected for a certain period.

Election and authorities of the rector – primus inter pares

A new rector was elected every semester at the University of Vienna – on the day of the saints Tiburtius and Valerianus (April 14) for the summer semester and on St. Coloman’s Day (October 13) for the winter semester. In 1629 his term of office was extended to a whole study year. The elections were held on St. Leopold’s Day (November 15), and from 1660 on St. Andrew’s Day (November 30). The procurators of the four academic nations elected the rector. To ensure that the four faculties participated in the university leadership as evenly as possible, the rectorate changed hands at regular intervals. Only members of religious orders were excluded from these duties. This arrangement was loosened in the 16th century, as was the restriction of the rector’s position to unmarried men. In the summer semester of 1534 the first married man was elected rector.

The rector was the highest representative of the university. Internally, he governed the university assembly and the Consistory. He also exercised the university’s jurisdiction over its members and led the university’s accounts. Since the end of the 15th century, the rector was addressed with the honorific “magnificus”, which has been preserved until today in the title of “Magnifizenz”.

Despite this wealth of competences the rector was no absolute ruler in his academic realm, but primus inter pares, first among equals: Apart from the sub-corporations that took part in the university administration, the church as well as the local sovereign tried to exert influence on the university through their representatives.

The university chancellor

Medieval universities were clerical institutions, which is why the local bishop or a representative of his choosing had a right to supervision of the university. At most universities, this supervision was a purely formal matter or was subject to severe restrictions.

In Vienna, the dean of St. Stephen’s cathedral held the office of university chancellor. His main capacity was to oversee exams and to grant authorization to teach to the licentiate and doctorate candidates. Often the chancellor delegated this power to a deputy, which led to arguments with the university, since these deputies sometimes had not graduated themselves. A serious dispute between the chancellor and the university broke out at the beginning of the 16th century, when the cathedral’s dean Paul of Oberstein demanded primacy over the rector and the right to utilize it. In the course of the fight against the reformatory ideology the chancellor took control of the university members: Since 1581 he accepted the graduates’ profession of faith to the Catholic Church and since 1649 he took their oath on the dogma of Mary’s Immaculate Conception. In the 18th century the chancellor’s authorities were cut by abolishing the old doctorate oath and the Catholic confession of faith. In 1873 his office was restricted to the Faculty of Catholic Theology.

The royal superintendent

The beginnings of this royal supervisory position are connected to the university’s first dotation by Duke Wilhelm: After he had allocated a yearly 800 guilders to the university from income from the toll at Ybbs in 1405, he decided that the administration and distribution of this money should be done by his representative. The university, however, received the right to choose a candidate itself.

This official first was known as “conservator”, later as “superintendent”. Since the administrators of various individual foundations also were called superintendents, the Duke’s representative became known as “landesfürstlich” (the Landesfürst was the local sovereign), and later “imperial” superintendent.

Through Ferdinand I’s reform laws his position was strengthened considerably: Since 1533 changes to the foundation’s finances were dependent on his approval, and in 1537 he obtained control over all of the university’s finances. Instructions for the superintendent, published in 1556, defined the financial administration as his main task. Because this included paying the professors’ wages, he also controlled the university teachers’ activities. In 1754 the office was suspended after its duties were divided between the study directors of the faculties and the university treasurer.

From the university assembly to the Consistory

In the university’s early years decisions were made by all doctors and licentiates. Votes on business decisions were held separately by the faculties; a majority was necessary to reach a decision. Baccalarii, students and academic citizens were usually not eligible to vote and were excluded from the assemblies. Only in matters of payments by the university all university members were allowed to vote.

Besides the general university assembly there also was the Consistory, which at first mainly dealt with matters of jurisprudence. Apart from the rector, the deans and seniors of the four faculties, as well as the procurators of the academic nations were members. Over time the university assembly delegated more and more business decisions to the Consistory, which in turn gained importance. In 1481 the university assembly decreed that Consistory decisions were equally ranked to decisions of the general assembly. In the course of the university reforms under Ferdinand I in 1534 the Consistory was confirmed as the university’s central authority. The university chancellor and the royal superintendent also received chairs in the Consistory. Together with the rector they were designated “consistorial dignitaries” (proceres consistorii).

Among other things, the consistory was the university contact for various royal and government offices and addressee for their decrees. The matters these decrees concerned were either directly decided upon in the Consistory or were passed on for review by the faculties. After the arbitration, the Consistory returned the results to the appropriate office.

With the incorporation of the Jesuit College into the university and the subsequent subordination of the Faculties of Philosophy and Theology under the order’s control, the rector of the Jesuit College also received a place in the Consistory. He was, however, excluded from the election of the rector actively and passively.

Changes in the 18th and 19th centuries

The reforms suggested by Gerhard van Swieten not only led to massive changes in teaching, but also in the administration. Besides changes in the faculties’ leadership and the university’s financial administration, the university leadership was also affected by this. The Consistory, until that point responsible for the whole of the university administration was divided up into two institutions in 1752: The “Consistory for legal matters” consisted of the rector and the procurator from the Faculty of Law (either the incumbent or a former procurator), the dean, as well as six advocates appointed by the local sovereign, who served as assessors. Here, the university’s civil and criminal legal cases were adjudicated. The “regular Consistory”, whose members included the rector, the faculties’ study directors as well as – just like before – the deans, seniors and procurators, was responsible for all other matters. This division became redundant with the abolition of the university jurisprudence in 1784.

In the 19th century, the reforms initiated by Leo Graf Thun-Hohenstein again led to profound changes in the organization of the academic authorities, which also affected the university leadership. The most important changes concerned the rector’s election and the Consistory’s composition, which was more often being called the “academic senate”.

With the abolition of the academic nations in 1849 the rector could no longer be elected by the procurators. The consistory stepped in as the voting authority. It consisted of the rector and the prorector (the current rector’s predecessor), the deans and vice deans as well as of representatives from the professors’ collegiate and until 1873 the doctors’ collegiate. While the rector (just like the deans) was elected every year, the term of the professors in the senate lasted three years. The academic senate was still responsible for all tasks concerning studies, discipline and administration.

-

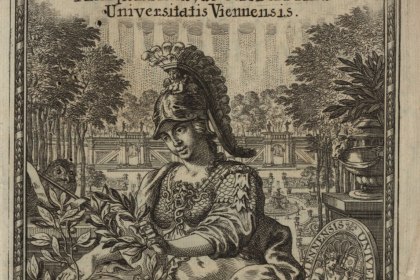

Sitzung des Universitätskonsistoriums

Der Stich zeigt eine Sitzung des Universitätskonsistoriums gegen Ende des 17. Jahrhunderts. Der Text auf dem Bild hat programmatischen Charakter. Der...

-

Szepter des Rektors der Universität Wien (1558)

Das Wiener Universitäts- oder Rektorsszepter stammt aus dem Jahre 1558. Der silberne, teilweise vergoldete, sechsseitige Schaft wird von vier Knäufen...

Zuletzt aktualisiert am 03/05/24